Building Giga: What Quantum Computing Means for High Performance Chains

By Ben Marsh of Sei Labs

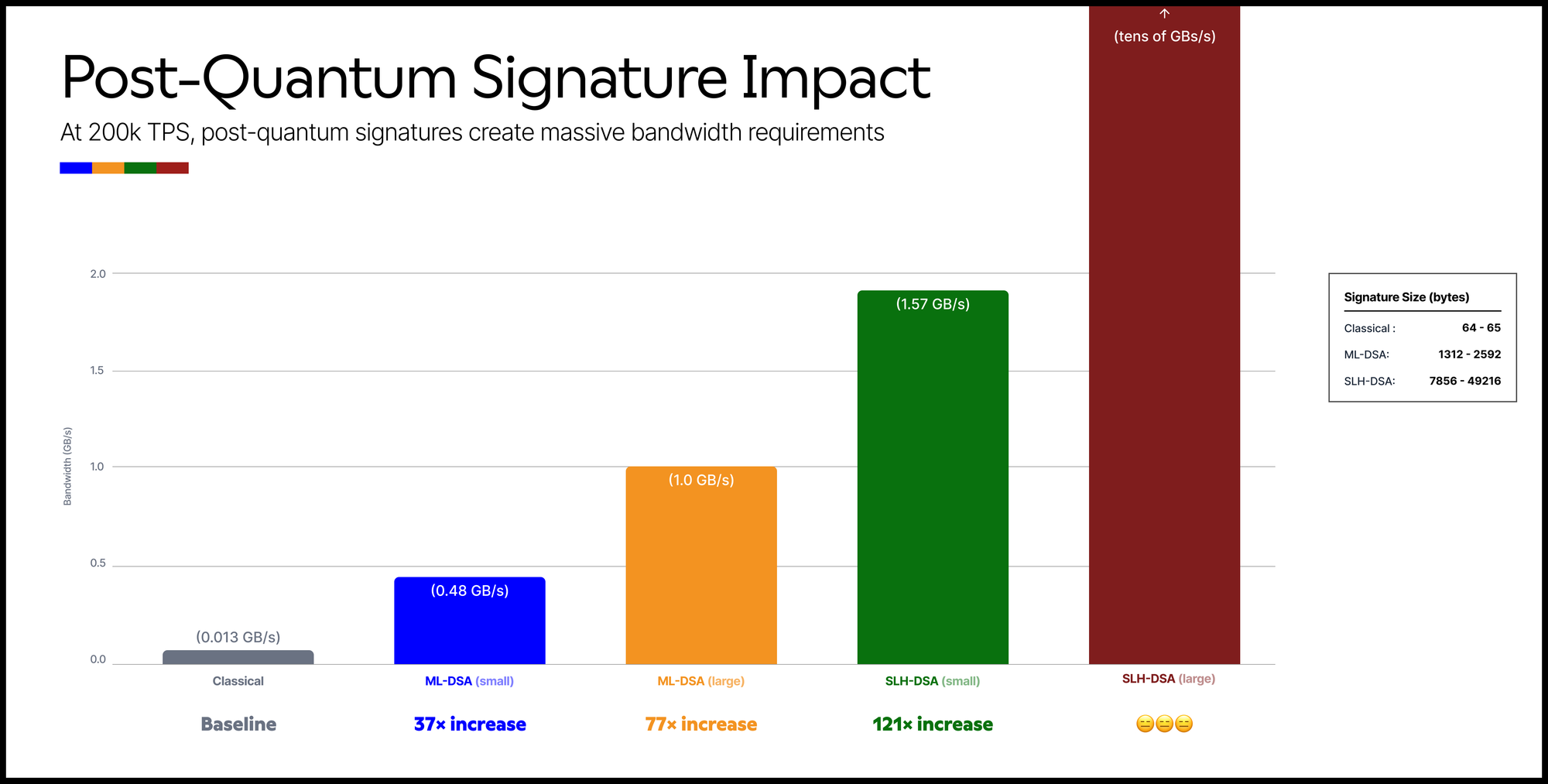

TL;DR: The Quantum Scaling Challenge for High-Performance Chains

Post-quantum security is a throughput problem, not just a math problem. Upgrading Sei Giga (200k TPS) to standard NIST post-quantum signatures (ML-DSA) would bloat bandwidth requirements to 0.48–1.57 GB/s, breaking the chain’s performance. The viable engineering path likely lies in zk proofs to batch verification off-chain, or optimistic "verify later" models protected by economic bonds. But the biggest challenge of a so-called "Q-day" may be the human element.

The Reality of Quantum Scaling

If you follow quantum computing, you already know that an algorithm called Shor could eventually make it practical to forge the digital signatures that protect most crypto wallets.

My work as one of the protocol researchers building Sei Giga has forced a sober conclusion about post-quantum security: most of the discourse is dumb because it treats quantum computing as a problem solved entirely by math, i.e., swap one signature scheme for a post-quantum secure one. But at Giga scale, the size and verification cost of those signatures would obviate the entire idea of a high-performance, low-latency chain.

This is not a panic piece or a hype piece about Sei Giga; it’s an engineering-first tour of what quantum capability would actually break, why the obvious fixes get impractically expensive when you have a chain with Internet-like performance, the constraints that creates for chain design, and approaches for solving the problem.

Giga

First let’s spend a little time talking about Giga, or a Giga-esque chain, and what can be done to deal with quantum computing in that context.

This is our setting: Giga is a 200k TPS EVM chain which uses ECDSA and Ed25519. Unlike Ethereum, Giga does not rely on BLS or aggregation in any form, or KZG commitments, which makes our life a little easier, as that’s fewer things to fix. The good news for Sei is that only the signatures break outright; Grover’s algorithm may weaken hashing to some extent, but we don’t rely on any encryption, so there’s no real risk of stashing data to decrypt later. With a cryptographically relevant quantum computer, Shor will give us a poly time attack on problems we currently consider to be computationally hard, such as the discrete log problem to which Sei’s current signature scheme, ECDSA, reduces.

That gives us a nice, well defined surface area to discuss: (1) User signatures which are currently ECDSA, (2) validator signatures that are currently Ed25519, and (3) the inevitable and unenviable upgrade path.

Let’s start with a little math.

- ECDSA signatures are 64 bytes, 65 in our setting with the recovery ID, with a 33 byte compressed public key that can be derived.

- Ed25519 signatures are 64 bytes with a 32 byte public key.

- With 40 validators, (the bare minimum needed to run a decentralized network) a “full set” of signatures over a single tip cut is, therefore, 2560 bytes, as we don’t aggregate, and each PoA of f+1 signatures is 896 bytes with a PoA required for every block in the tip cut.

- At 200k TPS the total bytes per second sum to 13,000,000/s.

- If we assume 3 tip cuts and 300 blocks for those 200k txs then we come to a total of 13,273,984 bytes/s, assuming 2f+1 votes per tip cut, which is approximately 13MB/sec.

The vast majority of that is from the users, so let’s stick with them for now.

If you want “standard post-quantum compute,” NIST has now finalized two digital signature standards that are directly relevant here, namely, ML-DSA (module lattice, derived from CRYSTALS-Dilithium) and SLH-DSA (stateless hash-based, derived from SPHINCS+).

Although quantum secure, there’s an obvious issue with these choices once you look at the public benchmarks and parameters. The signatures are huge in comparison. In FIPS 204 (ML‑DSA), the signature length for the smallest parameter set (2420) is 1312 bytes and for the largest (4627) is 2592 bytes. In FIPS 205 (SLH‑DSA), the signature lengths start at 7856 bytes for the smallest parameter set listed and climb into the tens of kilobytes for others (49216 is in the table of parameter sets).

So let’s redo our maths. A “small” ML‑DSA signature at 2420 bytes is 484,000,000 bytes/s ≈ 0.48 GB/s of signature data alone. The larger ML‑DSA parameter sets push you toward 1 GB/s. The “small” SLH‑DSA signature at 7856 bytes is 1,571,200,000 bytes/s, roughly 1.57 GB/s, and that’s the floor, not the ceiling.

At Giga’s scale those signature schemes mean that the chain becomes almost a signature DA layer with an EVM attached to the side somewhere.

The next question one might ask is, What if we ignore NIST? It’s not an unpopular question. In that case you tend to end up with isogenies such as SQISign, which have had some issues in the past, and smaller lattice schemes like Falcon. In the SQISign the signatures are only 204 bytes, with public keys of 64 bytes. This instantly brings our signatures back down to just a couple of times the size of today’s ECDSA. So, where’s the downside? Well isogenies, SIKE specifically, have a checkered past, at best, security-wise, meaning some will always balk at the idea.

To be clear, SQISign is not SIKE. The SIDH attacks that broke SIKE in 2022 exploited the public torsion point information that SIDH required for its key exchange structure. SQISign operates in a fundamentally different regime where it uses the quaternion algebra structure of supersingular isogeny graphs to compute endomorphism rings, and the signature is a proof that you know a secret isogeny without revealing auxiliary torsion data. The attack surface is genuinely different, and the scheme has held up under substantial cryptanalytic attention since. With that said, isogenies as a field are young and the “unknown unknowns” concern is not irrational, it's just not the same concern as “SIKE broke therefore isogenies are broken.”

But let’s assume they are secure, as I am somewhat comfortable believing these days. Are there any other blockers? The verification time for SQISign is 50ms per signature. At 200k TPS that’s 10,000 core seconds of work per second for just verification. On a 192 core AWS Hpc7a that’s 52 seconds of signature verification every second, assuming you do nothing else. This feels at least somewhat problematic.

Proofs Instead of Signatures

So given the above, what is it that we’re actually able to say? The obvious takeaway is that at Giga scale, a signature per transaction is too hard to do right now. The most straightforward way to do that is to stop putting raw signatures on chain as the first-class proof of authorization, and instead move to proofs where users (or aggregators) produce a succinct proof that “every transaction in this batch is authorized under the relevant post-quantum rules,” and the chain verifies that proof.

This is where STARKs and other post-quantum transparent proof systems start looking as attractive as Ethereum has pretended they are for years. The zk‑STARK line of work explicitly targets transparency and post-quantum security assumptions in the random oracle world rather than discrete log pairings. If your authorization scheme’s verifier is “mostly hashing”, and SLH‑DSA is literally a stateless hash-based signature standard, then proving verification inside a hash friendly proof system is at least directionally sane in a way that nothing else so far has appeared to be.

So what would this look like? Block production (or a dedicated prover market) batches a large set of post-quantum signature verifications, generates one proof attesting that they’re all valid, and posts only the proof plus minimal public inputs. Then you recurse, so “many proofs become one proof,” until your chain is checking something roughly constant size per tip cut. Given the recent work on recursion for zero knowledge provers, we know this is feasible. SLH‑DSA, SHPINCS+ or whatever else you fancy calling it, was that big hash-based signature I bullied before for pushing >1.5GB/sec in signatures through Giga. If the plan is now, let’s prove it, the stateless hash based structure of SLH-DSA looks promising. Now SLH-DSA uses SHA-256 as the base hash function, which the Ethereum L2s have been fighting for a long time, as it’s not the nicest hash to prove. We do, however, have zk-friendly hash functions such as Poseidon, so, in principle, and with a little juggling and security work, a prover friendly SPHINCS+ version could exist.

Commit Now, Verify Later

Giga is also slightly different in that it relies on lazy execution, and this opens a design space worth exploring more carefully. The core idea is hash commit now, verify post-quantum compute later. Blocks commit to transaction payloads and their purported authorization witnesses via hashes, and the network only does expensive post-quantum verification when it actually needs to execute or finalize state transitions.

In the optimistic case, where all transactions are valid, you never pay the full post-quantum verification cost at consensus time. The catch is obvious, though, and any semi-talented attacker would first try to stuff spam into the system to force you to do the expensive part. You need a mechanism where invalid or unavailable witness data reliably burns someone's money, and burns enough of it that the attack is too expensive to be practical. This starts to resemble optimistic patterns, but with a crucial difference: unlike fraud proofs, where the adversary is a sequencer with reputation and collateral, here the adversary can be any user, and the mempool itself becomes an attack surface.

One idea is that transactions enter the mempool with a post-quantim witness hash and a bond. Proposers include transactions optimistically, committing only to the hash. During a challenge window, anyone can demand witness revelation for a subset of transactions. If the witness is valid, the challenger loses their challenge bond. If the witness is invalid or unavailable, the transaction is reverted and the original sender's bond is slashed. The economics need to be set such that the expected cost of attacking exceeds the expected cost of honest post-quantum verification, and the challenge game doesn't itself become a griefing vector. There are subtleties here around who pays for verification when challenges occur, how you handle witness availability in a sharded or parallelized execution model, and whether you can batch challenges efficiently. But the broader point is that this reframes post-quantum compute from a pure cryptographic problem into an incentives problem, and incentives problems are arguably more tractable than waiting for cryptographers to hand us a 64-byte post-quantum signature with sub-millisecond verification.

Looking Ahead

Everything above—proof batching, recursion, commit-now-verify-later—quietly assumes you can ship the fix with minimal friction. But this is a case where the “simple” solution isn’t exactly easy. Post-quantum security is a distributed systems problem stapled to a coordination problem; you can’t just upgrade millions of keys the way you would a library. Once you accept that, the scariest part stops being the cryptography and starts being the upgrade path.

Until now, I’ve glossed over the thing that scares me the most: Migration. None of the clever crypto means anything if you don’t, or can’t, move users over to it. This topic deserves its own post, but one possible migration plan for Giga is to let users attach a post-quantum key to their existing identity before the so-called Q-day. That means some kind of dual key model where, in the pre-quantum era, an ECDSA account can authorize a binding to a post-quantum verification key, and for a long window both authorization paths are valid. Then, when you finally flip the switch and turn off ECDSA, you close the classical path and leave only post-quantum. This does leave an enormous problem, though: What do we do with users who don’t sign a new key in time?