Using Stablecoins Makes the Fed Your Bank

By Ben Marsh of Sei Labs

Summary

In the 20th century, the U.S. exported inflation and crises through trade, oil, and Treasury markets. In the 21st, it exports them through code. The rise of dollar backed stablecoins means that the same monetary system which prices U.S. mortgages, equities, and Treasury bills increasingly prices the rest of the world’s digital transactions too. The dollar should no longer be considered just a reserve currency it is becoming a settlement layer. When people “use stables,” they are not only holding a dollar, they are adopting a dollar balance sheet, with the Federal Reserve’s decisions embedded in its yield curve and the on-chain cost of time. Every user, merchant, or protocol that settles in USDC or any other USD denominated stable implicitly plugs into the Fed’s front end. It is a quiet form of dollarization instantaneous, frictionless, and invisible to the capital account.

The macro implication is straightforward but underexplored thus far. Once the world’s medium of exchange is dollar pegged, the world’s inflation and liquidity cycles are dollar driven. The Fed becomes, in effect, the world’s retail bank.

This post builds a formal backbone for that idea. If stablecoins spread across economies that still issue their own money, what happens to local monetary sovereignty? To answer that we define several channels where each of these channels can be independently explored. A CES CPI aggregator for goods pricing, a “digital UIP” for financial parity, and a queuing model for blockspace as a dollar indexed market. Together they form a system where stablecoin adoption turns the Fed’s policy rate into a global parameter.

We attempt to frame the obvious intuitions formally in this work. Section 1 sets conventions. Sections 2–5 formalize adoption and the digital UIP link. Section 6 embeds them in a small open New Keynesian block. Section 7 shows why blockspace itself behaves like a dollar yield instrument, and Sections 8–9 add fiscal and banking feedbacks. The conclusion pulls these into a simple, if uncomfortable, corollary that with stablecoins, no country can simultaneously maintain monetary sovereignty, digital openness, dollar trust, and price stability.

As dollar backed digital money becomes a medium of exchange far beyond America’s borders, it silently extends the reach of the Federal Reserve into every wallet and balance sheet that touches it1 . The transmission operates through three intertwined channels. First, a goods pricing channel, as more consumption and trade are invoiced in dollars, local prices begin to move with U.S. inflation. Domestic CPI increasingly reflects the Fed’s stance, not the local central bank’s. Second, a financial channel, a “digital UIP” emerges, linking domestic short rates and exchange rate dynamics directly to the U.S. front end, with the strength of that linkage rising with stablecoin penetration. Third, a microstructural channel, even on-chain, blockspace fees are effectively quoted in basis points of notional value. They co-move with U.S. short rates and network congestion, tying the cost of digital activity itself to U.S. monetary conditions. We extend this backbone with models in which the currency of invoicing is endogenous, a small open New Keynesian block yields closed form passthrough elasticities, and seigniorage and bank funding channels complete the macro transmission.

Conventions and Notation

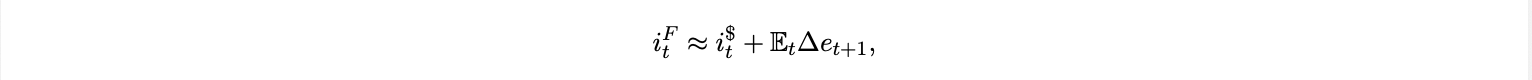

Time is discrete, t = 0, 1, 2, . . . . For a scalar Xt , define ∆Xt ≡ Xt − Xt−1 and, for price indices, πtX ≡ ∆ log Xt . Et denotes local currency units per USD. We set et ≡ log Et and ∆et ≡ et − et−1 . Thus ∆et > 0 is a local depreciation. πt$ is US inflation, πtL is inflation of the domestically priced sub-basket, and πtC is headline CPI. i$t is the USD short rate (policy/bills), iFt is the domestic short rate, and ist is the stable/wrapper USD yield accessible to households. We allow a wrapper basis δt ≥ 0 so that

We collect convenience/regulatory frictions that favor local money into a wedge ζt ≥ 0. Let A ∈ [0, 1] parameterize stablecoin adoption. Adoption raises the USD pricing share and lowers frictions:

When needed, we use parametric forms

Let Rt ∈ [0, 1] denote a merchant acceptance index for USD stable checkout.

Adoption

The key adoption fact is stark, by mid-2025, nearly all stablecoins by market value are pegged to the U.S. dollar. In practice, “using stables” means using dollar units of account and settlement rails. This raises the USD-priced share of the CPI aggregator, i.e. the weight ω in 3. To make the channel explicit, let the CES aggregator evolve with a time varying USD pricing weight ωt ∈ [0, 1]:

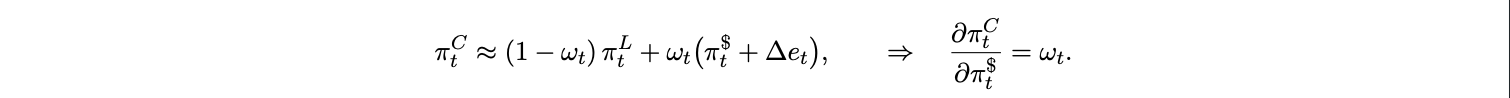

Under a first order log-linearization around the base point,

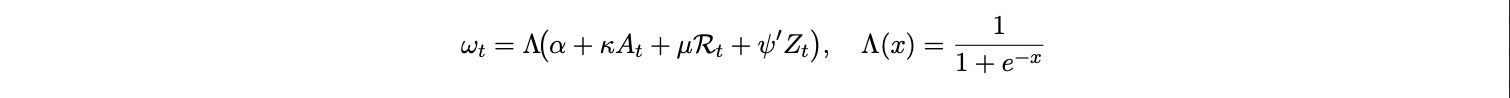

Stablecoin adoption is the mechanism that moves ωt . Denote by At a country time adoption intensity. We parameterize the USD pricing weight as a logistic map:

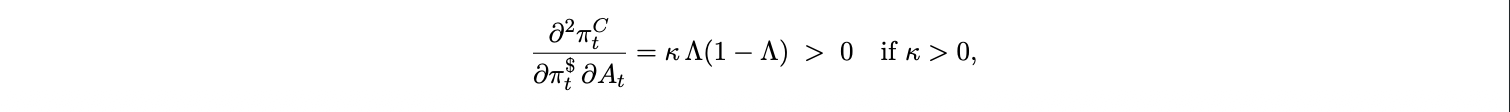

with Zt controls (trade invoicing patterns, import composition, regulation). Provided κ > 0 and µ > 0, adoption and merchant rails strictly raise ωt away from the corners. Combining the previous two equations yields an immediate comparative static:

so the static pass-through coefficient in Prop. 1 becomes adoption state dependent. Adoption itself is endogenous to macro conditions. In the short run, the FX leg in the static pass interacts with a digital UIP for non-interest-bearing stablecoins,

where iFt is the foreign policy rate, ist the implicit stablecoin yield, and ζt frictions (convertibility premia, on/off-ramp spreads, controls). A U.S. tightening that lifts ist lowers Et ∆et+1 even if impact-period overshooting raises ∆et on impact. Empirically, stablecoin net outflows from the U.S. to the rest of the world rise when the dollar strengthens, indicating digital dollar demand. To discipline identification, we treat adoption as a diffusion with state-contingent accelerants:

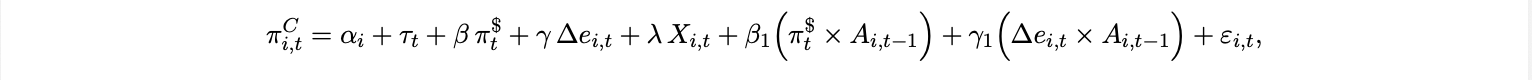

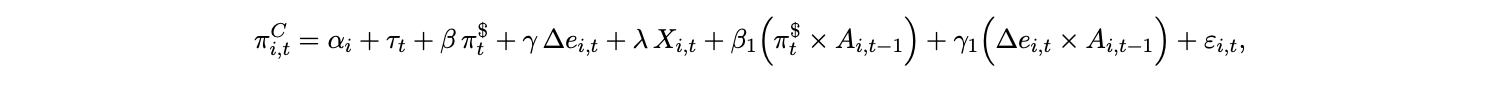

with a country-specific ceiling A⋆ ≤ 1. Currency weakness (∆et > 0), domestic inflation, and higher U.S. yields can all push adoption upward by raising the shadow value of USD settlement and hedging against local currency risk. Substituting the above into the adoption law and time variant CES from 2 produces a tractable dynamic link from global dollar conditions to πtC via ωt . At monthly or quarterly horizons, a minimal reduced form that captures the cross-regime prediction above is

with country and time effects (αi , τt ) and controls Xi,t . The testable implications are therefore β1 > 0 as adoption raises static pass-through to U.S. inflation, and γ1 > 0 if the FX leg bites more when a larger share of the basket is USD-priced. Event time dummies for rail rollouts and issuer/exchange shocks proxy for ∆ωt shifts that are plausibly exogenous to domestic price setting at short horizons.

For At , we use on-chain and off-chain proxies for the USD pegged share of activity, aligning the metric with the logistic map, (i) the share of retail or professional-sized transfers involving stablecoins in Chainalysis’ regional series, (ii) the ratio of stablecoin flows to GDP at the region level, and (iii) the share of exchange activity in USD stable pairs from market micro data. For Mt , we use merchant acceptance coverage dates of payment-processor integrations that switch checkout into USDC/PYUSD and rollouts across platforms. Differences in metric definitions are documented and controlled for in Zt or via instrument sets.

This implies that the dollar’s sway over local CPI scales linearly with ωt . With the dollar’s share near 99% of stablecoin market value and mainstream merchant rails switching on USDC/PYUSD checkouts, At and Mt do not merely coincide with dollar adoption they are its mechanism. Under dominant currency pricing, higher USD invoicing raises pass-through, the before maths simply port that logic to the CPI aggregator. On the data, the direction is unambiguous, and the magnitude is large enough to matter at policy frequencies.

Tl;dr

People reach for stablecoins when the local currency looks shaky, when inflation bites, or when U.S. rates climb and safe dollar yield is one click away. Merchants follow when acceptance costs fall and checkout in digital dollars gets easier. As this spreads, a larger slice of everyday prices and invoices move into dollars. That shift matters because it forces U.S. conditions into local outcomes, the more you live in dollar units, the more local inflation and exchange rates react to U.S. moves. Adoption is therefore both a symptom of stress and a cause of tighter dollar linkage.

CPI Pass-through via USD Pricing

We start with goods pricing as the most direct channel through which stablecoins transmit U.S. monetary conditions abroad. The logic is straightforward, the more of a country’s consumption basket is invoiced or denominated in dollars, the more its local inflation mechanically moves with dollar prices and the exchange rate. Consider a CES aggregator between a domestically priced component with index PtL and a USD priced component with USD price index Pt$:

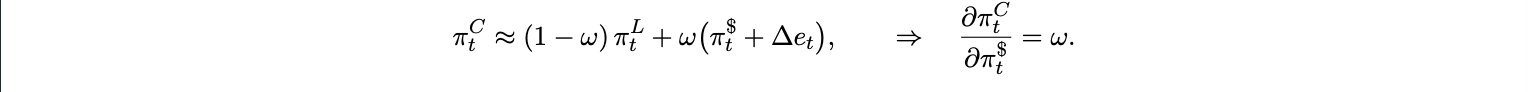

Let ω denote the base period expenditure share on USD priced items evaluated at the linearization point.

Proposition 1 (Static pass-through).

This expression states the immediate intuition a percentage point increase in U.S. inflation translates into an ω-fraction increase in the local CPI, scaled by the share of the basket that is USD priced. If 40% of what a country consumes is invoiced in dollars, then roughly 40% of U.S. price shocks feed directly into its CPI, before accounting for any policy reaction2 . On impact of a US tightening, standard overshooting suggests ∆et > 0, lifting πtC via the FX term. In expectations, a digital UIP gives Et ∆et+1 ≈ iFt − ist − ζt , so a higher i$t (hence higher ist ) tends to lower Et ∆et+1 . The sign of the dynamic FX contribution depends on timing, its magnitude scales with ω and with wedges (δt , ζt ). This is the skeleton key of the argument. Everything else the adoption model, the UIP link, the blockspace pricing simply endogenizes or amplifies this coefficient.

Tl;dr

The more a country’s shopping basket is quoted in dollars, then the more likely its consumer price index naturally tracks U.S. inflation and the dollar’s ups and downs. On impact, a Fed tightening often pushes the dollar up, imported dollar prices then jump in local currency terms, and headline inflation ticks higher. Over the next few months, expected moves in the exchange rate can offset part of that, but the basic point is that the dollar share of pricing governs how much U.S. inflation “shows up” in local CPI. Push that share higher, and local policy has less room to keep domestic prices insulated.

Endogenizing the USD Pricing Share ω

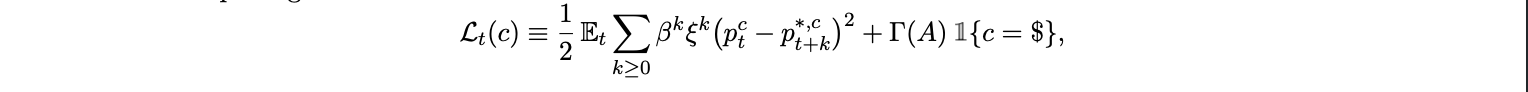

In the previous section we treated ω, the share of consumption priced in USD, as exogenous. In reality, ω is not fixed, it is an equilibrium object shaped by firm level currency of invoicing decisions. Firms weigh expected price stability, settlement convenience, and payment acceptance when choosing whether to invoice in local currency or in dollars. Stablecoin adoption affects all three margins at once reducing volatility in dollar settlement, improving network liquidity, and lowering transaction costs thus endogenizing ω. We model currency of invoicing as a dynamic choice under nominal rigidity. In each period, a measure 1 − ξ of firms reset prices. A firm that resets chooses a currency c ∈ {L, $} and a reset price pct to minimize its expected discounted quadratic loss from mispricing:

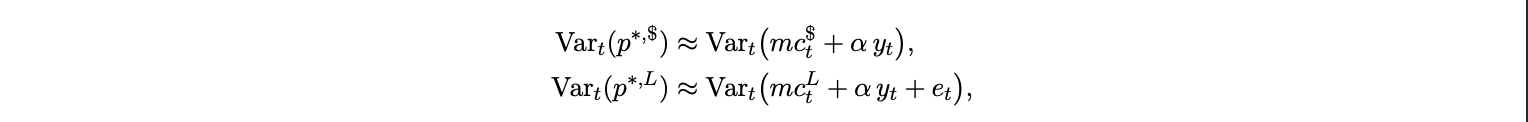

where pt+k is the desired (log) price in currency c, β ∈ (0, 1) is the discount factor, and Γ(A) captures the net cost of quoting in dollars, decreasing in adoption A (so Γ′ (A) < 0). The term Γ(A) summarizes settlement frictions, regulatory costs, and acceptance premia that vanish as stablecoins become ubiquitous. Under standard approximations, desired prices track expected marginal costs and output:

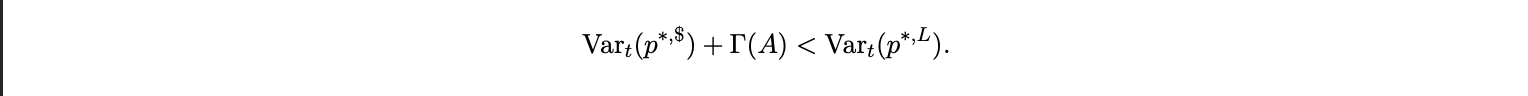

so the expected volatility of optimal local currency prices rises with exchange rate volatility. A firm thus prefers USD invoicing when

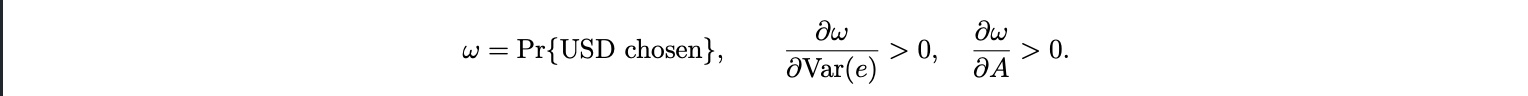

The above equation defines the firm’s invoicing choice. Dollar invoicing becomes more attractive when either (i) exchange rate volatility Var(e) rises, or (ii) adoption A reduces the cost of dollar settlement Γ(A). Aggregating across firms gives the equilibrium USD pricing share:

Proposition 2 (Endogenous ω). Under the previous equation, the equilibrium USD pricing share ω is increasing in exchange rate volatility and in adoption A. As stablecoin adoption lowers Γ(A), more firms choose to price in dollars, raising ω and amplifying the CPI pass-through t$ from Proposition 1.

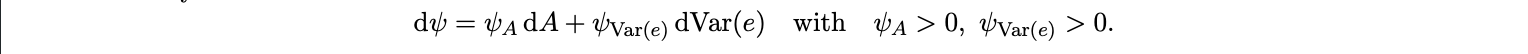

Intuitively, stablecoin infrastructure transforms dollar invoicing from a costly niche behavior into a frictionless default. Once settlement and acceptance are digital, quoting in dollars becomes both safer and simpler for firms exposed to FX risk. The result is a feedback loop, higher adoption lowers Γ(A), increases ω, and strengthens the mechanical coupling between local inflation and U.S. monetary conditions. Differentiating the static pass-through coefficient ψ ≡ t$ = ω(A, Var(e)) yields

Hence any rise in stablecoin adoption A or in exchange rate volatility directly steepens the slope of CPI pass-through to U.S. inflation. So the first lever goods pricing scales with how firms invoice. The next lever, asset substitution, scales with how households save. Both tilt the same way towards the dollar as adoption rises.

Tl;dr

Firms prefer dollars when they fear exchange rate swings or when dollar settlement is cheap and widely accepted. Stablecoin rails lower the hassle and risk of billing and collecting in dollars, so more firms flip their invoices over time. That creates a feedback loop, as dollar invoicing grows, pass-through from U.S. conditions strengthens, which makes local currency risk more salient, which pushes even more firms into dollars. The unit of account drifts toward the dollar unless something interrupts this loop.

Currency Substitution and Digital UIP

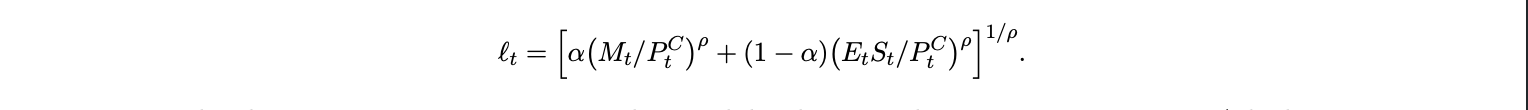

The second transmission channel operates through portfolio choice and interest rate parity. As stablecoins circulate alongside local money, households hold a mix of domestic currency and USD denominated digital assets for liquidity and savings. Their portfolio decisions determine how closely domestic short rates shadow U.S. rates through a “digital UIP” condition. Households choose {Ct , Mt , St } to maximize expected lifetime utility

where liquidity services are produced by a CES aggregator over local money balances Mt and USD pegged stablecoin balances St:

The elasticity parameter ρ governs substitutability between the two monetary assets. A higher ρ means domestic money and stablecoins are close substitutes in liquidity provision. The household faces the budget constraint

where iFt is the domestic short rate, ist the stablecoin yield (linked to the USD short rate i$t ), and Φt ≥ 0 captures regulatory, compliance, or cross-border friction costs that scale with stablecoin use. In equilibrium, risk neutral arbitrage between the two cash like instruments implies a modified interest parity condition.

Proposition 3 (Digital UIP with wedges). To first order,

Adoption lowers both wedges: ∂δt /∂A < 0 and ∂ζt /∂A < 0. In the frictionless limit (δt = ζt = 0), the parity reduces to

which is the textbook uncovered interest parity condition. As the adoption of USD pegged stablecoins rises, these wedges narrow and domestic monetary conditions increasingly co-move with those of the U.S. Economically, δt represents a stablecoin specific spread reserve yield retention, custody frictions, or credit risk while ζt captures policy and regulatory wedges such as capital controls, KYC constraints, or limited on/off-ramp access. Both act as barriers insulating the domestic rate from U.S. short rates. As digital infrastructure matures and stablecoins become mainstream, these barriers weaken, tightening the link between local and U.S. front end rates. In other words the “digital UIP” closes the classic gap between emerging market short rates and U.S. rates. When stablecoins dominate transactional liquidity, the local monetary authority’s ability to maintain an independent rate path erodes, since any deviation triggers arbitrage or substitution into USD denominated assets on-chain.

Tl;dr

As adoption rises the average household will hold two kinds of cash like assets, local money and digital dollars. When it’s easy to move between them, the local short rate gets pinned to the U.S. short rate plus whatever depreciation people expect in the local currency adjusted for any policy or plumbing frictions that remain. As those frictions shrink with adoption, this parity tightens. Try to run local rates too far from the U.S. front end and people will switch into whichever side pays more after currency risk.

A Minimal NK-SOE with Digital UIP

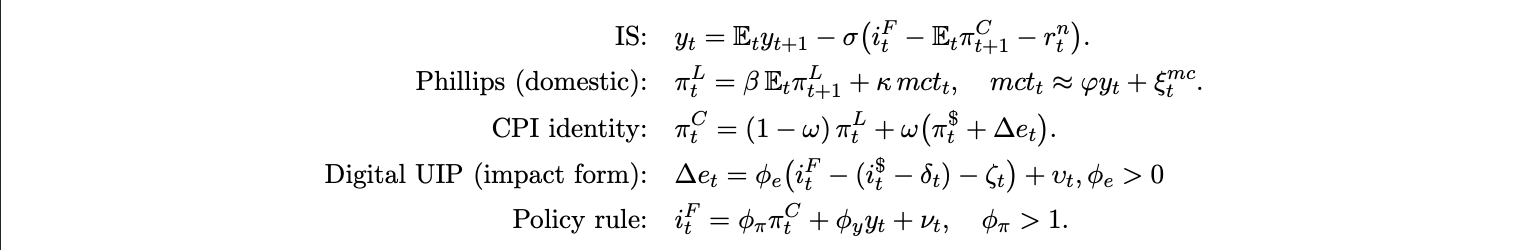

We now embed the preceding components in a minimal small open New Keynesian block. This structure closes the model and produces transparent, closed form expressions for CPI pass-through elasticities that can be used to quantify how stablecoin adoption amplifies U.S. monetary spillovers. The system combines a standard intertemporal IS curve4 , a domestic New Keynesian Phillips curve, a CPI identity linking local and USD priced components, a reduced form “digital UIP” for exchange rate dynamics, and a Taylor style policy rule:

As such we define the impact elasticity of the spot exchange rate to the interest differential as ϕe . Under the classic Dornbusch overshooting view, ϕe ≈ 1. For algebraic clarity, we abstract from output feedback by setting yt ≈ 0 and hold πtL locally fixed.

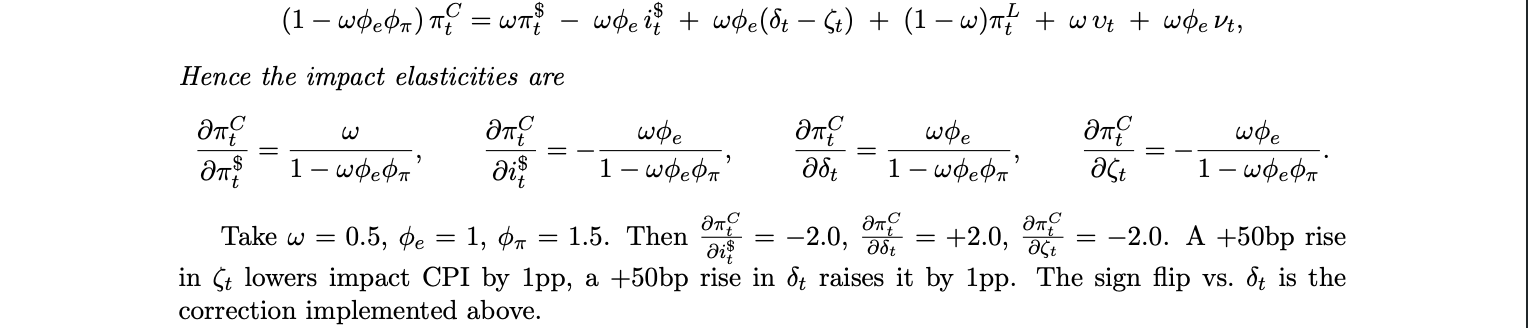

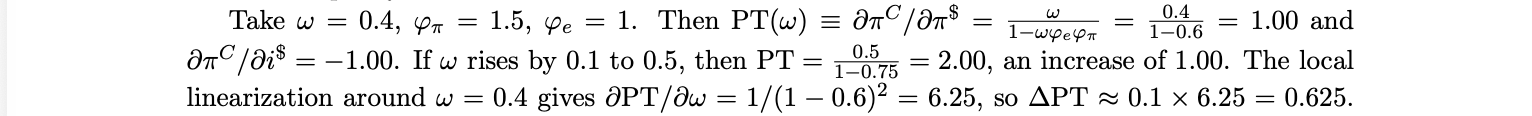

Proposition 4 (Closed form impact pass-through). With yt and πtL held locally fixed,

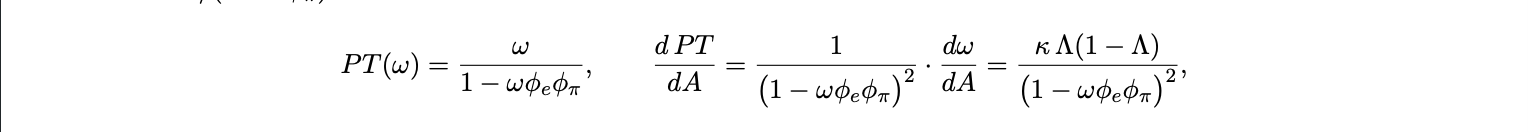

Thus it is shown that stablecoin adoption amplifies foreign monetary transmission through ω and ϕe . The denominator 1 − ωϕe ϕπ captures the feedback loop between imported inflation and local policy response, a higher ϕπ paradoxically increases the degree of pass-through by feeding back into the CPI via the exchange rate. With ϕe = 1 and wedges fixed, define P T (ω) ≡ ∂πtC /∂πt$ = ω/(1 − ωϕπ ). Then

where Λ = Λ(α + κA + µR + ψ ′ Z) and ω = Λ so adoption raises pass-through and does so convexly in ω due to policy feedback.

Thus a modest increase in dollar pricing share produces a disproportionate rise in CPI sensitivity to U.S. shocks. The result formalizes the our previous intuition that once a significant fraction of domestic pricing and liquidity is dollar denominated, local inflation reacts almost one for one to U.S. conditions. Stablecoin adoption magnifies this link by raising ω and tightening the digital UIP channel, effectively substituting the Fed’s reaction function for the local one.

Tl;dr

In summation, dollar based pricing transmits U.S. inflation, interest rate parity channels the U.S. front end, and the local policy rule feeds back through the exchange rate. The result is a stronger domestic reaction to inflation can amplify pass-through when much of the basket is in dollars, because rate moves spill into the currency and back into CPI. As the dollar share of pricing rises and parity frictions fall, the sensitivity of local inflation to U.S. shocks grows nonlinearly. Past a threshold, “doing more” at home delivers less control.

Towards Blockspace Priced in Basis Points

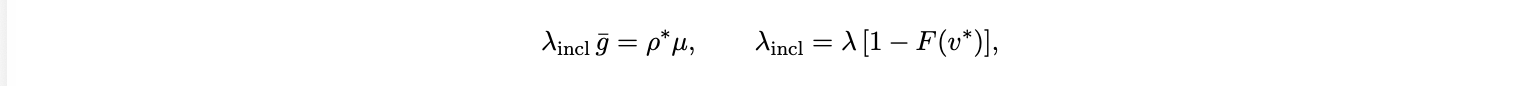

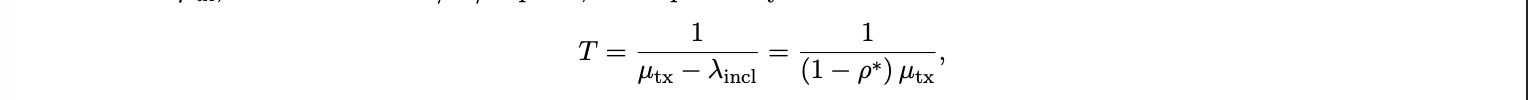

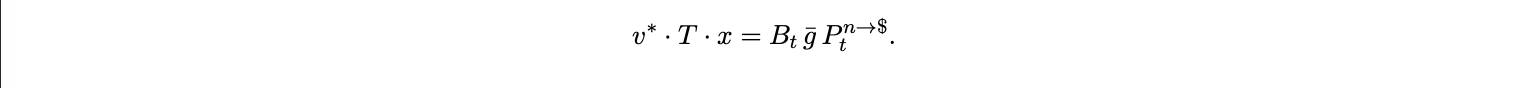

Even if a country walls off its goods and financial sectors, digital settlement itself carries a yield curve. Blockspace becomes a de facto dollar market. Even without explicit dollar invoicing or cross border asset substitution, the cost of transacting on-chain is effectively quoted in basis points of notional value, a form of implicit monetary indexing. Because value of time and opportunity cost are denominated in dollars, the front end of the U.S. yield curve directly anchors on-chain fee levels. Transactions i arrive at rate λ with notional xi (USD), gas demand gi , and value of time vi . Capacity is µ gas/sec, and with average gas per included transaction ḡ, the system can process

transactions per second. Under a 1559 style transaction fee mechanism5 , blocks target utilization ρ∗ ∈ (0, 1). In a steady state,

where F is the CDF of value of time vi and v ∗ is the marginal cutoff for inclusion. Intuitively, transactions with higher vi bid in, those with lower vi wait. With effective arrival λincl and service µtx , modeled as an M/M/1 queue, the expected system time is

so that T is finite and pinned by the utilization target ρ∗ . The protocol design keeps queueing delay roughly constant, which means base fees must adjust to keep ρt near ρ∗ . Let Bt be the base fee and Ptn→$ the USD price of the native token. A marginal included transaction with average gas ḡ is indifferent when the dollar cost of waiting equals the dollar cost of inclusion:

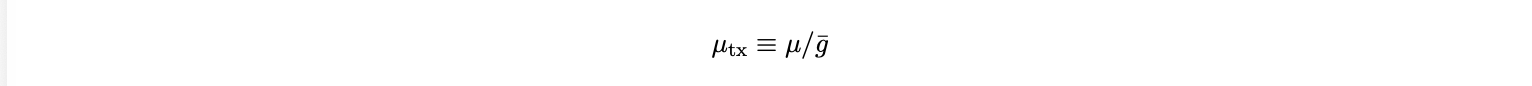

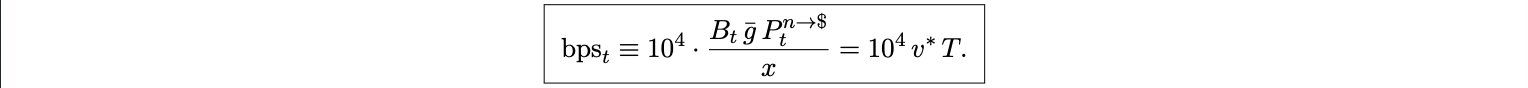

Define the fee per notional in basis points:

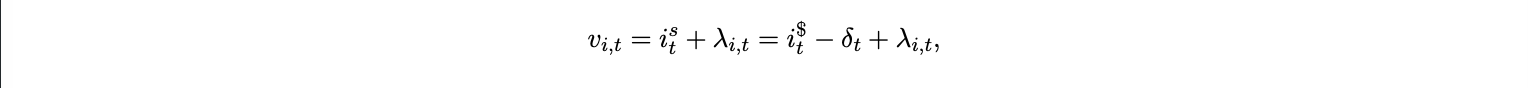

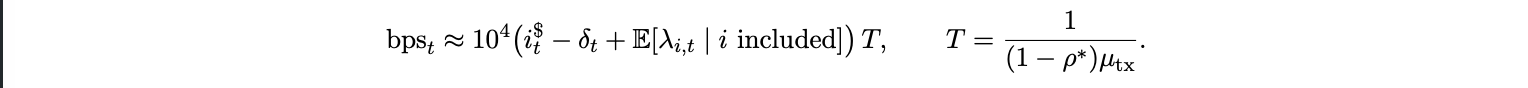

Throughout, i$ and is are annualized rates, T is the expected time to inclusion in years. With these units, bpst is dimensionless and interpretable as basis points of notional. Thus the implicit “interest rate” of transacting is the opportunity cost of time, scaled to basis points of transaction size. A reduced form for the value of time is

where λi,t captures idiosyncratic latency, MEV, or risk of reordering hazards. Conditioning on inclusion gives

Because T is fixed by protocol parameters, a rise in U.S. short rates i$t or in on-chain velocity shifts the inclusion cutoff v ∗ upward, increasing bpst . Stablecoin velocity magnifies this effect by thickening the right tail of vi transactions settle faster and bid more aggressively for blockspace. Let realized utilization be ρt . A standard 1559 control law is

with ρt = min{1, λt [1 − F (vt∗ )]ḡ/µ}. A front end U.S. rate shock thus transmits to bpst through two legs a fast leg via v ∗ (the immediate repricing of time value and a slow leg via Bt , as utilization overshoots and the controller raises the base fee. The previous equation makes the link explicit, the unit cost of transacting on-chain moves with the U.S. short rate i$t , even in purely domestic usage. When stablecoins dominate denomination and settlement, blockspace effectively becomes a dollar indexed commodity. The same front end rate that prices Treasury bills now prices access to digital settlement capacity. We treat T as years. When using T = ( 1−ρ1∗ )µtx , measure µtx in transactions per year.

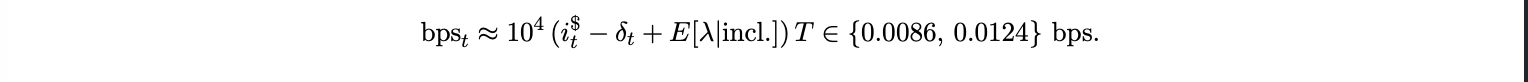

Let T be the expected inclusion plus finality window in years. If T = 10 minutes ≈ 1.9 × 10−5 years, δt = 0.5%, and the idiosyncratic hazard term contributes E[λi,t |incl.] = 2%, then with i$t rising from 3% to 5%,

At very low T (fast L2s) or very small notional x, absolute fee floors can dominate, breaking the proportional to notional intuition.

Tl;dr

The auction setting of a blockchain means users either wait or pay to jump the queue, protocols target a steady utilization, so fees adjust to clear demand. When the value of time in dollars rises, because U.S. short rates are higher or on-chain urgency spikes it holds that users bid more to be included, and the effective fee per dollar of transaction value climbs. Stablecoins amplify this because they attract higher velocity, dollar denominated activity that competes for blockspace. Even if a country tries to ring fence the real economy, the digital plumbing still inherits the U.S. yield curve.

Seigniorage and Fiscal Feedback

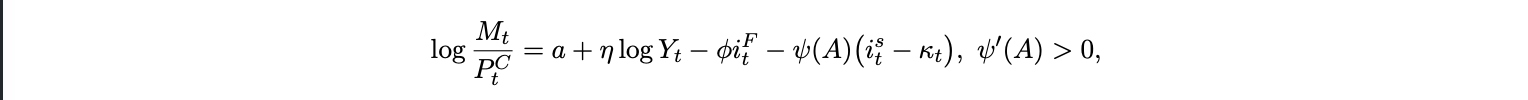

Let real money demand be

where κt is a per unit stable friction. Real seigniorage is st ≡ (Mt − Mt−1 )/PtC ≈ µt (Mt−1 /Pt−1 with µt money growth. Adoption raises ψ and lowers δt , reducing real money demand for given iFt and eroding seigniorage. Thus, as adoption A rises (so ψ(A) increases and frictions κt fall), a higher stable yield reduces real money demand, eroding the seigniorage base.

Proposition 5 (Seigniorage erosion). Holding fiscal needs fixed, an increase in adoption A lowers real money demand and the seigniorage base, shifting the government’s intertemporal budget toward taxes, borrowing, or higher inflation. Thus adoption can increase local inflation incentives even if the stablecoin itself does not pay explicit interest.

Bank Funding and a Credit Spread Channel

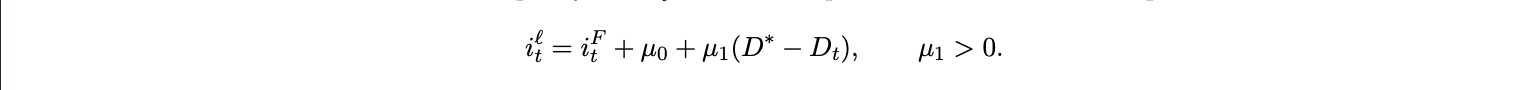

The final transmission channel operates through the banking system. As households substitute from deposits into yield bearing stablecoins, banks lose a cheap and stable funding base. Unless they can replace it through wholesale markets, the marginal cost of credit rises and passes into prices through the Phillips curve. Households allocate between domestic deposits earning idt and stablecoins yielding ist − τ (A), where τ (A) represents the effective friction conversion cost, on/off-ramp constraint, or regulatory risk that declines with adoption (τ ′ (A) < 0). A simple linear deposit supply schedule is

where χ measures interest elasticity and ϵt captures shocks to deposit preferences. Banks fund loans at the policy rate iFt but face a spread that widens when deposits are scarce:

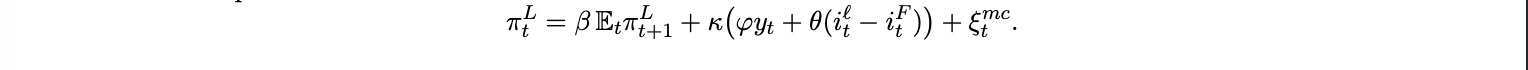

The loan rate iℓt thus embeds a credit premium that rises as deposit flight intensifies. Because marginal cost in the New Keynesian Phillips curve includes financing costs, this spread becomes a cost push term:

Hence, when adoption lowers τ (A) and deposits Dt fall, loan spreads widen and inflationary pressure rises even without demand shocks. In effect, digital dollarization creates a credit channel amplification of monetary transmission. This channel mirrors the “flight to yield” problem faced by banks in highly dollarized economies, when a parallel USD denominated store of value becomes easily accessible, domestic deposit bases shrink and lending margins rise. Stablecoins replicate this mechanism in digital form, linking on-chain financial openness to offline funding fragility.

Tl;dr

Stablecoins siphon traditional bank deposits away, especially when dollar yields are easy to capture and conversion is painless. If banks replace lost funding in wholesale markets, their costs rise, if they don’t, credit shrinks. Either way, loan rates move up relative to policy rates, and that wedge pushes into prices through firms’ costs. The digital dollar doesn’t have to “invade” lending to change the credit channel the drain on deposits is enough.

The Impossible Quartet with Digital Openness

Once you tie the goods, portfolio, and microstructural legs together, the policy constraint surfaces automatically. The models above imply a unified constraint on policy. Once digital dollars circulate freely, a country cannot simultaneously preserve all of the following, monetary independence, FX stability, capital account openness, and banking sector stability. Combining the digital UIP with an FX stability objective gives a simple bound. To keep expected FX changes within ±ε:

As stablecoin adoption rises, the openness parameter d falls digital capital flows become frictionless. Unless the central bank relaxes either its FX stability objective (ε ↑) or its policy independence (m ↓), the bound above binds. Adding banking sector stability as a fourth objective makes the trade off sharper, tighter capital controls preserve funding bases but sacrifice openness, while openness drains deposits and raises spreads. In classical macro econ, the “impossible trinity” ruled out simultaneous exchange rate fixing, capital mobility, and monetary autonomy. The web3-ified world adds a fourth leg, the stability of domestic intermediation. Stablecoins collapse the capital account barrier not through banks but through code . The result is a digital “impossible quartet” no country can maintain all four at once once stablecoins reach scale. Suppose a central bank targets ε = 1pp and faces ū = 0. If adoption is low, (δ, ζ) = (1.5%, 1.5%) ⇒ d = 3%, so m ≤ 4% is feasible. If adoption rises and wedges narrow to (0.4%, 0.6%) ⇒ d = 1%, the bound tightens to m ≤ 2%. A policy aiming for m = 2.5% becomes infeasible unless ε is relaxed or d is raised.

Policy levers map one for one into the wedges, including, raising ζ (e.g., tighter convertibility/KYC frictions or ramp quotas) restores monetary space and FX stability but sacrifices digital openness, raising δ weakens substitution into stables and dampens the UIP channel, but shifts seigniorage to issuers and can push activity off-shore, lowering ω by re-domesticating the unit of account via retail CBDC corridors or domestic currency stable rails reduces CPI pass-through at the cost of fragmentation and potential liquidity discounts, banking backstops can offset the funding channel externality without directly closing rails.

Conclusion

The models above converge on the idea that when settlement, savings, and pricing migrate into digital dollars, U.S. monetary policy ceases to be a foreign variable. Stablecoins transform the Fed’s stance into a global parameter. Through goods pricing, portfolio substitution, and on-chain microstructure, the short end of the U.S. curve penetrates both domestic price indices and the cost of transacting digitally. In the short run, this linkage is invisible, a frictionless means of exchange that simply “works.” In the medium run, it exports the Fed’s tightening and loosening cycles worldwide. And in the long run, it challenges the very notion of monetary sovereignty. For policymakers, the choice is not between banning stablecoins and embracing them. It is between designing institutional buffers that reintroduce local monetary frictions capital controls, taxation asymmetries, or CBDC corridors and conceding that digital openness implies imported policy. The conclusion is uncomfortable but clear, in a world of frictionless dollar rails, using stables means using the Fed’s balance sheet as your own.